Learning to Live in a New World

In the previous issue of Aberdeen Magazine we learned about Sioux Chief Waneta who was born and lived north of Aberdeen near Frederick. In this story, we follow the saga of Chief Drifting Goose as he faces immigrant encroachment onto his homeland. He was the last bastion of resistance to white settlers and the railroad in the Aberdeen and Brown County area.

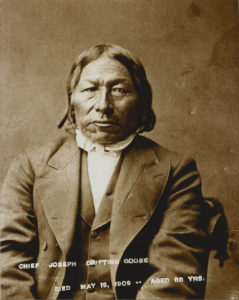

A photograph of Chief Drifting Goose, taken in the late 1800s by Charles Milton Bell. Photo courtesy of The Center for Western Studies, Augustana University.

Magabobdu, or Drifting Goose, was a Hunkpati Sioux chief who kept Eastern South Dakota relatively free from settlers and railroads until the 1870s. He was notorious for resisting settlers and disrupting the work of railroad surveyors, but he did so without using extreme violence. He cared deeply for the survival of his people, and for his home along the James River. He is the only chief in history to receive his own reservation, and the only chief of the plains tribes who never signed a treaty. Drifting Goose is famously attributed with saying that he had signed nothing, so consequently, gave up nothing. His life is replete with tales of activities aimed at “unwelcoming” settlers. He could speak Nakota, Dakota, Lakota, and English, as well as understand some of the settlers’ languages, such as German. He was well respected and known as a highly intelligent, caring, peaceful, and friendly man.

Early Life on the James River

Drifting Goose was born in 1821 in the James River Valley just north of present-day Redfield. His people controlled an area from eastern Minnesota to the Missouri River, and from Sioux Falls north to roughly Sand Lake. Nearby, Waneta and his people controlled the James River Basin from Sand Lake north to Pembina. Drifting Goose and Waneta’s bands were friendly with each other, interacted frequently, and utilized each other’s territories.

As a young man, Drifting Goose learned the skills of debate, bargaining, persuasion, and diplomacy from his father, Wounded, and other tribal members by attending the annual gathering of the Seven Council Fires at Council Rock, located just north of Redfield. Council Rock was a sacred spot where the Sioux tribes would gather to discuss issues, trade, and share time together. It was considered a safe zone and anyone who was in need was taken care of there.

In 1840, at age 19, Drifting Goose became chief of his people. Two years earlier in 1838, Waneta had abandoned the northern part of the James River Valley and moved his people to Emmons County, North Dakota, leaving his former territory to Drifting Goose. Prior to this time, Drifting Goose’s people were nomadic and had numerous campsites up and down the James River. With this new territory to oversee, Drifting Goose decided a new permanent home was needed that was centrally located to control the area from Sioux Falls to Jamestown. That year, he moved his people further north up the bank of the James to an area called Armadale Island, which is just northeast of Mellette. It was a location that featured abandoned earth lodges that had previously been used as seasonal quarters, most likely by the Arikara who had migrated west to the Missouri River in the mid-to-late 1700s. This area also featured good stands of timber, fertile soil for crops, and abundant game. They settled in nicely to their new home, planted crops, and hunted the scattered groups of bison that roamed west of Aberdeen.

Deterring Settlers

During the 1840s, more and more settlers poured into Minnesota, violating the 1825 Treaty of Prairie du Chien. Despite protests by the various bands of Sioux, nothing was done to curb the influx of immigrants. Minnesota had been made a territory and Alexander Ramsey was appointed its governor. He, along with Luke Lea, Commissioner of Indian Affairs in Washington, D.C., pushed the Sioux to sign a treaty ceding large amounts of land to the United States Government in return for other considerations. After considerable pressure and the continuing influx of settlers into Indian territory, the Sisseton-Wahpeton Sioux signed the Treaty of Traverse des Sioux on July 23, 1851. The treaty ceded lands in southern and western Minnesota along with some lands in Iowa and Dakota Territory. Drifting Goose refused to participate in the treaty negotiations, and upon hearing of the details of the treaty he was furious. Some of the land ceded by the Sisseton-Wahpeton in Dakota Territory was not theirs to give; it was already home to Drifting Goose and his people.

As a result of this treaty, settlers did try to move into Drifting Goose’s territory. Shortly after the signing of the treaty in 1851, the Dakota Land Company from St. Paul and the Western Land Company from Iowa attempted to establish a town at present-day Sioux Falls. A small group of surveyors and investors moved in and started planning and staking out the area. Drifting Goose and his warriors plagued their encroachment efforts from day one. They would pull up survey sticks, take or damage equipment, and run off livestock. For the next five years, Drifting Goose would disrupt these intruders, until 1856, when enough settlers, along with a detachment of soldiers, arrived to secure the town site. During the time from 1851 to 1862, Drifting Goose also discouraged any settlers who ventured into the James River Basin and effectively kept them out without actually hurting anyone.

The Dakota War of 1862

Beginning in 1861, a lot of things changed for Drifting Goose and the Sioux people. First, what is now North and South Dakota was designated as Dakota Territory. The Civil War also broke out that same year. Then in 1862, the Homestead Act was passed offering free land to people who would file a claim in Dakota Territory. But the biggest thing was the so-called Dakota War of 1862 that erupted on August 17 of that year on the Sisseton-Wahpeton Reservation in Minnesota. When supplies ran short on the reservation the Sioux became desperate and resisted the settlers. Minnesota Governor Ramsey commissioned Henry Sibley and ordered him to subdue any resistance by the Sioux. After a three-week period of battles between Sibley’s men and the Dakota Sioux, the “uprising” was indeed subdued and the Sioux were ultimately punished for trying to survive and hold on to their homelands. Sibley requested a mass execution from President Abraham Lincoln for 239 Sioux women and men whom he had hastily tried in a kangaroo court. Lincoln communed all but 38 men who were put to death by hanging on December 26, 1862, in Mankato, MN. This travesty remains the largest execution in U.S. history.

As a result of this uprising, all Dakota were banished from Minnesota and a $25 bounty was put on all Dakota found in Minnesota Territory. This caused a frantic movement of Dakota Sioux into Dakota Territory. Drifting Goose assisted many to move through his territory, provided they remained peaceful. Upon hearing of the hostilities in Minnesota, the investors, settlers, and soldiers who had secured the site of Sioux Falls in 1856 abandoned it and moved to Yankton by the end of 1862.

Tensions and minor hostilities remained prevalent throughout the James River Valley for the next few years, and Drifting Goose had his hands full keeping the peace and trying to keep his homeland from being overrun.

The Move to Crow Creek Reservation

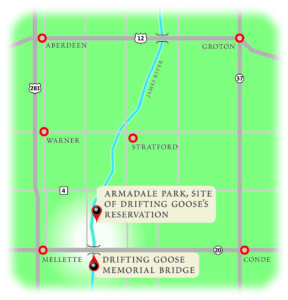

President Rutherford Hayes granted Drifting Goose’s request for a permanent 65,000-acre reservation near Armadale Park in 1879. A year later, Hayes reversed his executive order and released Drifting Goose’s reservation, and homeland, into public domain for settlement.

In 1868, the Fort Laramie Treaty was brought to Fort Rice for signatures, which resulted in the Sioux moving to designated reservations of their choice. All Sioux leaders signed the treaty except one: Drifting Goose. He refused. Instead, he focused on his village at Armadale. He replaced the earth lodges with sturdy log cabins designed for defense, and planted crops on the surrounding fertile land. But all was not well. Some of his people thought they should abandon their home and move to the reservation. As chief, Drifting Goose could have ordered them to stay, but instead he held a meeting of all his people at which they could speak freely about what they wanted to do. A fair number of them wanted to move to the reservation, so Drifting Goose allowed them to do as they wished, and 169 families left for the Standing Rock Reservation. Despite this loss, Drifting Goose persevered.

From 1869 on, more and more settlers attempted to move into the territory near his home, as did surveyors for various railroad lines. Again, Drifting Goose obstructed all those who came onto his land, especially the railroad surveyors, and his efforts became legendary, known as the “Drifting Goose War.” He pulled out stakes at every turn, released livestock, cut fencing, stole and damaged equipment on a regular basis, and, on one occasion, stripped a surveyor of his clothing and sent him off in nothing but his birthday suit. While hostilities escalated between Indian nations and white settlers in western parts of South Dakota, Drifting Goose’s eastern side of South Dakota was relatively quiet.

In addition to battling encroaching settlers, Drifting Goose and his people endured hardships caused by drought and locust infestations for a few years during the 1870s. Then, in 1878, Drifting Goose received an order that he must leave his home on the James River and report to the Crow Creek Indian Reservation. Because of the hardships experienced over the previous years, he reluctantly agreed and abandoned his cabins and crops and went to Crow Creek with minimal military escort. Upon arriving there, Drifting Goose and his people were given land allotments, standard rations, and other annuities. They tried to settle into a new life.

On June 27, 1879, in an executive order, President Rutherford B. Hayes declared the establishment of the Drifting Goose Reservation. Granting a reservation to a specific individual was unheard of. The reservation site identified was Drifting Goose’s beloved Armadale area southeast of where Aberdeen would arise and near the Mellette area. Upon hearing the news, Drifting Goose and 104 of his family and followers returned to his home site only to find his cabins occupied by a good number of settlers, his crops harvested, the majority of the timber cut, and access to the river cut off. He camped there for a while, trying to convince the settlers that this was now his territory. The settlers refused to listen, and as fall came Drifting Goose moved his people to the Sisseton area, where they spent a difficult winter.

In the spring of 1880, Drifting Goose’s reservation was revoked by another executive order of President Hayes. He permanently abandoned Armadale as his home and left the area for good. He moved back to Crow Creek and settled onto land along the Missouri River. From 1880 on, Drifting Goose traveled freely from Crow Creek throughout eastern South Dakota, visiting with many of his settler friends, and stopping at various schools, businesses, and government offices. He was the only individual who could leave the reservation without specific permission from the Indian agent and written travel authorization papers. As Drifting Goose continued to travel, he became more and more convinced that education would be the salvation, strength, and future of his people. In 1886, this dream became a reality. Father Pierre DeSmet came to Crow Creek and, after extensive talks with Drifting Goose, established a missionary and built a school on the reservation.

Work in Later Years

U.S. commissioners and delegations of Sioux chiefs visiting Washington, D.C. October 13, 1888. (Library of Congress)

In 1888, Drifting Goose appears in a photograph on the steps of the old U.S. Capitol building with a large delegation of Sioux Chiefs visiting Washington, D.C., on October 15. This visit, unfortunately, occurred in response to the Dawes Allotment Act, which led to great land loss for the Sioux and a widespread influx of settlers.

Drifting Goose’s last visit to the James River Valley was in 1904, when he was invited to be the featured speaker at the settler’s picnic on the Fourth of July at Fischer’s Grove near Redfield. Dressed in one of the finest suits of the time, he spoke to the large crowd about his beloved homeland, events in his life, the establishment of his school in Crow Creek, and his relationships and experiences with many of his friends who were in attendance. In closing, he bid farewell to his James River, stating he would never return. With his last words, he also reminded those in attendance that, although he had been forced to give up his beloved land near the James, he had also spared the lives of many settlers in order to ensure the survival of his people.

Drifting Goose passed away in 1909 at the age of 88. He was buried in the Immaculate Conception Cemetery behind his school, which still operates today on the Crow Creek Reservation in Stephan, South Dakota. He is now credited with significantly changing South Dakota development in many areas and having more impact on government bureaucracy than any other representative of his people. His descendants continue to live at Crow Creek.

The bridge on Highway 20 that crosses the James River near Drifting Goose’s original home was named after the chief through the efforts of Aberdeen local, Dave Swain.

Today, at Fort Thompson there is a road named Drifting Goose Drive in honor of the chief. Since 2007, the Drifting Goose Rendezvous has been held each spring near Mansfield, which is close to Drifting Goose’s original Armadale village site. And in May 2011, Aberdeen resident Dave Swain, an avid historian, Drifting Goose fan, photographer, and Highway 20 tourism promoter, filed an application with the SD Department of Transportation that was approved, naming the bridge on Highway 20 that crosses the James River between Mellette and Brentford the Drifting Goose Memorial Bridge. // –Mike McCafferty

We would like to extend special thanks to Dani Daugherty for editorial assistance, David Swain, and the K.O. Lee Aberdeen Public Library.