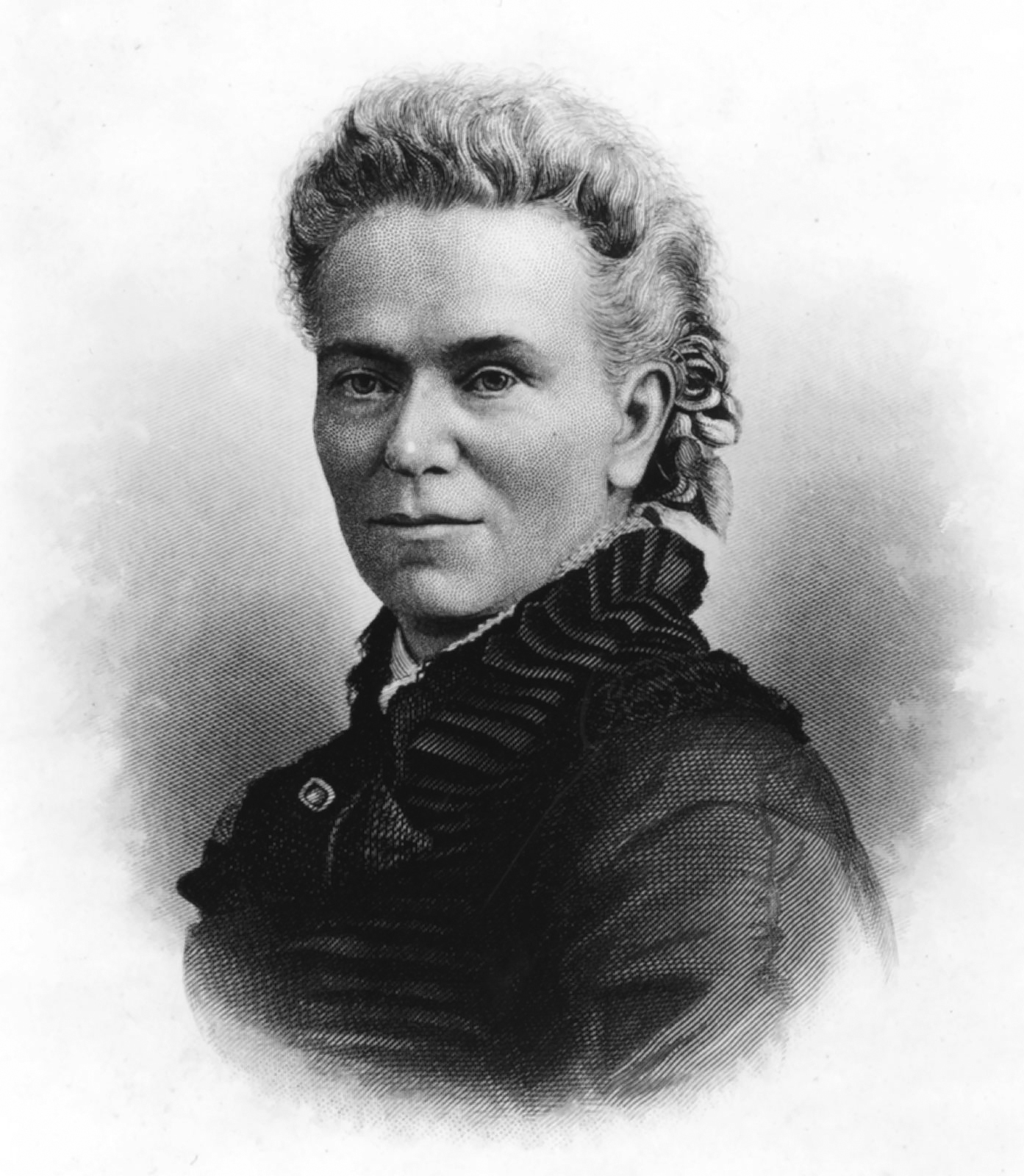

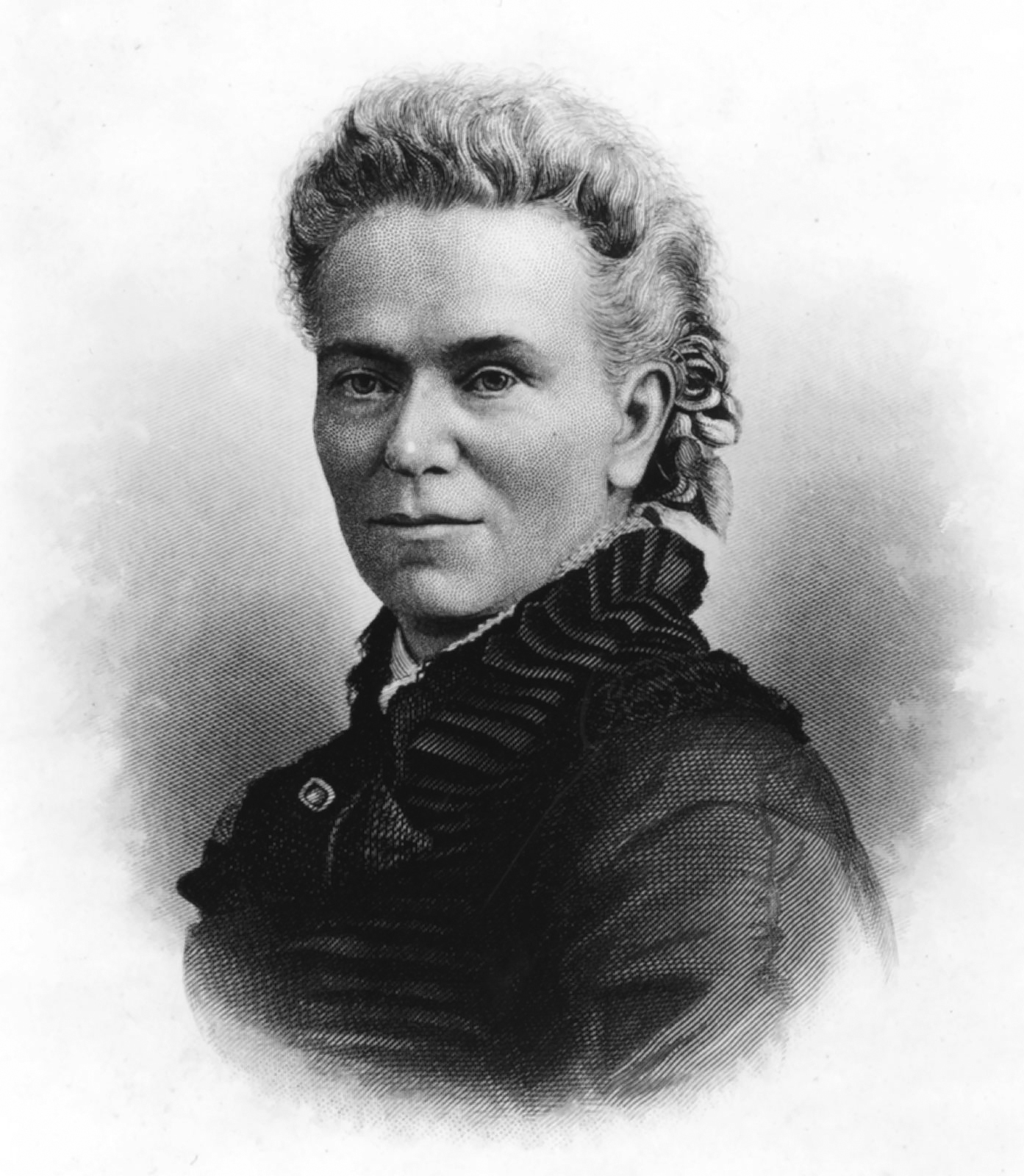

This year, women all over the country celebrate the centennial of Women’s Suffrage. Almost 40 years before that day in 1920 when women finally won the right to vote, Matilda Joslyn Gage, an instrumental suffragist leader, was advocating for the movement in Aberdeen and all of Dakota Territory.

In the summer of 1883, 57-year-old Matilda Joslyn Gage left central New York State and boarded a train for Dakota Territory. As the train rambled on, her view gradually changed from forests and rolling hills into fields of wheat and corn as far as she could see. Finally, reaching her destination, she stepped onto the unpaved streets of Aberdeen, a bustling frontier town with waves of new settlers and supply deliveries arriving daily by railroad.

It had been a long trip west, and the temperatures in Dakota were spiking in the upper 90s that summer. Matilda’s lodging in Aberdeen was an unfurnished apartment above the Beard, Gage & Beard Merchandise Store. Her door, and the only thing separating her from passersby strolling along the corner of Main Street and Third Avenue, was a blanket, and her washstand, a simple dry goods box. Above her, exposed rafters hung visible in the ceiling. The modest living quarters stood in stark contrast to Matilda, who always wore elegant dresses and stylish attire fit for a lady of her time.

Still, she was more than happy to be in Aberdeen. Her son, Thomas Clarkson, part-owner of Beard, Gage & Beard, caught “western fever” in years prior and had relocated here with a group of friends from New York, as had her daughter, Julia, who was living on a homestead near Edgeley. But it wasn’t just family that brought Matilda to Aberdeen. It was a fight she had already been battling for most of her life. But let’s back up to the beginning.

To say Matilda grew up in a progressive household would be an extreme understatement. Even when she was just nine years old, her parents allowed her to stay awake late into the night while they welcomed visitors into their central New York home. Some were slaves escaping to freedom in Canada, as the family’s house was a secret stop on the Underground Railroad. And, according to Born Criminal Matilda Joslyn Gage, Radical Suffragist, other welcomed guests included “Famous abolitionists, philosophers, and politicians” who gathered in the parlor to discuss “ideas that were outrageous for the time: outlawing slavery, granting women rights equal to those of men, and outlawing alcoholic beverages (the temperance movement advocated this move to overcome problems caused by drunkenness).” While most children were ushered out of these adult conversations, Matilda was encouraged to chime in with her own opinions and questions. Later she wrote, “I think I was born with a hatred of oppression, and, too, in my father’s house, I was trained in the anti-slavery ranks.”

Growing up, Matilda also spent time with her aunt Perry, who owned a store and traveled to and from New York City to purchase goods for the business. Working this type of job while married, as well as traveling alone, were radical lifestyle choices for a woman at that time. Watching her aunt, Matilda determined she too would earn her own money by following in her father’s footsteps and becoming a doctor. The only problem? Women weren’t allowed to attend medical school. Nevertheless, Matilda decided to enroll in a secondary school, with hopes that the regulations prohibiting women to study medicine would be lifted. In 1843, she completed her coursework at the Clinton Liberal Institute. She was ready to study medicine, but even with her father’s efforts and connections in the field, not a single medical school would accept her based on her gender.

The blow was deep. Matilda knew she had to do something to make sure other women, someday, would be permitted to study and practice medicine. And there were several more laws that troubled her even more. Women couldn’t own property, vote, or even have rights to their children if their spouse died. While these laws made others feel helpless, they only fueled in Matilda a tireless pursuit to change them.

It wasn’t long after that Matilda married store owner Henry Gage. The couple had four surviving children, Helen, Thomas Clarkson, Julia, and Maud, as well as one famous son-in-law who we all know as L. Frank Baum. In 1848, a group of suffragists hosted the Seneca Falls Women’s Rights Convention. Matilda opted to stay home and care for her young children instead of attending, but she continued to follow the movement closely in the newspapers while also maintaining her home as a safe place for runaway slaves.

Then in 1852, with her daughter Helen in tow, Matilda decided to in her own words “publicly join the ranks of those who spoke against wrong” by taking part in a women’s rights convention in Syracuse, New York. Also in attendance for her first convention was 32-year-old Susan B. Anthony. While many voices spoke that day about what women could do if only given the right, Matilda took a different angle. In her speech, she told of the many accomplished women artists, scientists, inventors, and leaders throughout history. She dismissed the argument that women had further to go in order to be equal members in society as men, and therefore capable of voting, and instead showed how women had already proven their adeptness time and again. She ended her speech by crying, “Onward! Let the truth prevail.” Most newspapers condemned the event. But 26-year-old Matilda was just getting started.

Up until her death at age 71, Matilda worked to secure equality for women, African Americans, and American Indians. She traveled to speaking engagements and collected signatures for petitions. She led civil disobedience movements and addressed congressional committees. She was a respected scholar and an essential organizer of suffrage associations. Perhaps her greatest gift to the cause, however, was her ability to write. Matilda penned countless letters and articles to newspapers and elected officials, presenting sound arguments for why women should be allowed to vote. Later, she would go on to publish her own newspaper, co-author History of Woman Suffrage with Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and author her own book Woman, Church and State.

When Matilda arrived in Aberdeen for the first time in 1883, Dakota Territory was preparing to divide into two separate states. Her mission? To ensure women’s rights made it into any new state constitutions. Laws in Dakota stated that a husband was “head of family” and that his wife had no rights to his land, even in the event of his death, or any claim to the homestead that she had helped build with an equal amount of sweat and tears. Matilda traveled throughout the territory, which proved difficult due to the large distances between towns, giving lectures and encouraging women to act now in their demand for equal treatment and rights at the voting poles. In a letter addressed directly to the Women of Dakota she said, “You have not been permitted to help make these laws which rob you of property, and many other things more valuable. Many women are settling in Dakota. Unmarried women and widows in large numbers are taking up claims here, and their property is taxed to help support the government and the men who make these iniquitous laws.”

Because of the work of Matilda and other suffragists in the territory, women in Dakota almost won the right to vote. But note quite. According to A History of Woman Suffrage Volume III, in the last legislature of 1885, Major John Pickler introduced a bill that gave women the vote. It easily passed in the House and the Council, but was later vetoed by Governor Gilbert A. Pierce. An effort to overturn the veto failed. Later, in a letter to Matilda, Major Pickler addressed the governor’s veto, stating, “I deeply regret that he did not rise to the grandest opportunity of his life, but he failed to do so.”

Matilda visited Aberdeen on many more occasions throughout her life. All four of her children lived here at one time, and two, Helen and Thomas Clarkson, are buried at Riverside Memorial Park. Some of her grandchildren grew up in Aberdeen as well, including a granddaughter named after her, Matilda Jewell. The Gage house, owned by Thomas Clarkson and later Matilda Jewell, still stands in the Hagerty-Lloyd Historic District today. Matilda often stayed here while visiting family in Aberdeen.

Women did not earn the right to vote during Matilda’s first visit to Dakota, but her work was not in vain. Today, her writings and lectures are referenced by human rights advocates worldwide. She was decades ahead of her time in speaking against the wrong treatment of all people, and because she had the strength to keep going, even after being told “no” time and again, the rest of us can replicate her courage in the face of adversity. Her motto lives on. “There is a word sweeter than mother, home, or heaven—that word is liberty.” // — Jenny Roth

Wait, Matilda Who?

Matilda Joslyn Gage may not be a household name when it comes to women’s suffrage, but she should be.

There is a saying that “Half of writing history is hiding the truth.” If you’ve never heard of Matilda, it’s likely because her face wasn’t the one you saw in photographs of women marching in the street and getting thrown into jail while trying to vote. Matilda was arrested for registering to vote, but her voice for women’s rights came through the most in her writing and in her many speaking engagements. It is also possible that you’ve never heard of Matilda because her colleagues Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, in a sense, wrote her out of her own story.

Matilda was outspoken in her beliefs on how the Christian church oppressed women and on her support of the separation of church and state. Many of her fellow activists felt uncomfortable with this and worried her views were damaging to the movement’s credibility. Both Ms. Anthony and Mrs. Stanton outlived Matilda, and in writing the history of women’s suffrage, they left her name off articles she authored, failed to give her sufficient credit in all instances she deserved, and downplayed her influence. When women finally won their right to vote in 1920, Matilda had already passed away over 20 years prior.

The good news is history can always be rewritten. Sally Roesch Wagner, an Aberdeen native and a pioneer in women’s studies, has collected research on Matilda for over 50 years. She also opened the Matilda Joslyn Gage Foundation in Matilda’s hometown of Fayetteville, New York (matildajoslyngage.org). Here, visitors can tour Matilda’s home and learn about her legacy. In 2018, the South Dakota historical Society Press published Angelica Shirley Carpenter’s book, Born Criminal Matilda Joslyn Gage, Radical Suffragist, a work that further solidifies just how much Matilda did for women’s and human rights everywhere. And, right here in Aberdeen, an exhibit replicating Matilda’s parlor in New York is set up in her honor for patrons to visit anytime at the Dacotah Prairie Museum.