When the U.S. Post Office and Court House opened in 1937, a flyer was circulated that said the building was “Ours to Use and Enjoy”—an optimistic view for a place that was mostly occupied by the forces of federal law and order.

Enjoying the courthouse myself and waiting to see U.S. District Court Judge Charles Kornmann, I watched six men in black-and-white striped prison suits out of a 1940s prison movie walk by, just sentenced by the judge and flanked by three or four officers. A court security officer wearing a bulletproof vest escorted me. He had also been wearing the vest a week earlier, before a man in Wisconsin who had broken into a private home, bound a retired judge, and murdered him. Judge Kornmann later mentioned that the windows near the security area are bulletproof.

Some may not be aware the building includes a courthouse. Over 80 years, weathering has almost hidden the building’s name engraved over the main doors—one door went to the one-time post office and the other to the once-touted “high speed” elevators to the upper floors, the only tenant of which now is the Federal Court.

Building History

Built in 1937 to replace the 1904 Post Office and Court House two blocks to its west on Main Street, this second federal building in Aberdeen faces Fourth Avenue SE between Lincoln and Washington Streets—such an auspiciously patriotic address that the third federal building parked itself across the street in 1974.

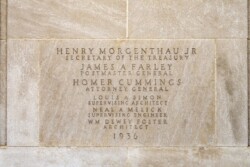

The nearly $500,000 building constructed during the Great Depression was called the “finest Post Office west of Des Moines.” Building materials included South Dakota granite from Milbank (at the request of the local postmaster) for trims and stone at the front entrances and butternut wood from South America for the judge’s chamber and courtroom.

The courtroom once had six large south-facing windows to let in daylight. Sadly, in the 1960s, they were covered over with bricks. On the back side of the building, overlooking the service area, the bricked-up windows might be less noticed, except for the stone framing and the lighter-colored bricks. But the not-windows create a perhaps unfortunate double-edged metaphor: Blind Justice to be sure, a court unbiased in its neutral quest for justice, but also maybe unmoved by the outside world in its deliberations. That, however, is an exploration for a different time in a different essay.

The five-story building went up quickly, with groundbreaking in December 1936 and dedication by U.S. Postmaster James Farley in October 1937. About 6,000 people took tours on Christmas, New Year’s Day, and the adjoining Sundays. The building housed the post office on the main floor; the IRS, FBI, U.S. Attorney, and various federal offices on second and third; the Federal Court on fourth; and the petit jury room (now the Federal Magistrate’s office) on the fifth.

Legal History

Why does Aberdeen have a Federal Courthouse? In 1911, Congress passed a law setting out one federal judicial district in South Dakota arranged in four divisions, identifying Aberdeen as the location for trials in the northern division. The division includes northeastern counties from the North Dakota border to a southern boundary of Deuel, Hamlin, Clark, Spink, Edmunds, Walworth, and Corson counties, as well as the Standing Rock and Sisseton reservations. Going up one judicial level, South Dakota is in the Eighth Circuit, based in St. Louis, which also hears appeals from Arkansas, Iowa, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, and North Dakota.

South Dakota had one federal judgeship for more than 60 years (not counting a brief period in the early 1930s). The early judges were based in Sioux Falls, but twice yearly heard cases in each division, which took them to Aberdeen, Pierre, and Deadwood (until the western division was relocated to Rapid City in 1974).

South Dakota has had 16 federal judges to date. The first to take up residence in Aberdeen was Axel Beck. Born in Sweden, he came to Alcester, South Dakota, alone at age 11 at the invitation of an aunt. With a University of Chicago law degree, he returned to South Dakota and was admitted to the bar in 1924. A leader in the Republican Party, when a 1957 law provided for a second federal judge in South Dakota, President Dwight Eisenhower appointed him in 1958. He moved to Aberdeen in 1959 and presided in Aberdeen and Deadwood.

After Beck took senior status—essentially retiring, although like many judges, he continued to hear cases—Don Porter, the judge in Pierre, handled Aberdeen for a while, as did judge Fred Nichol. Richard Battey, who was born in Aberdeen but raised in Frankfort, was appointed a federal judge in 1985 after 30 years of practice in Redfield in the firm of Gallagher [the author’s father] & Battey. He was elevated to federal judge shortly after Roger Wollman, another Frankfort product, had been named to the Federal bench. Battey served primarily in Rapid City but occasionally presided in Aberdeen.

A variety of criminal cases were heard in Aberdeen, many coming from Indian reservations. When tribal law does not apply, federal courts have jurisdiction. Drug cases are also common. Judge Battey heard the 1987 case in which men were found guilty of shipping cocaine to Aberdeen by FedEx. More recently, Judge Kornmann sentenced men for selling meth on the Sisseton Reservation.

Judge Kornmann

Chuck Kornmann’s route to the Federal bench was somewhat circuitous. Growing up in Castlewood, he attended law school at Georgetown University in Washington, DC, and got a job as a Capitol Police Officer thanks to then Representative George McGovern. During school, he worked the midnight shift guarding the locked U.S. Capitol building, which allowed him to study at night. When McGovern was defeated in 1960, Kornmann retained his job thanks to North Dakota Senator Quentin Burdick.

In 1963, after law school and McGovern’s election to the Senate, the now-married Kornmann joined McGovern’s staff, but only briefly, as he was asked to be executive director of the S.D. Democratic Party. He and his wife Caroline moved to Mitchell, where the state headquarters was. While there, he became a second lieutenant in the South Dakota National Guard.

In 1965, he left the Party job for Aberdeen and the Voas, Richardson and Groseclose law firm. “Our office was in the Milwaukee Depot Building, and we had free rent and the best law library of any private law firm in the state,” he recalls. They represented the South Dakota Railroads Association as lobbyists in Washington, DC, and Pierre. This began Kornmann’s 30-year lobbying career.

Thirteen years later, the bench started to beckon. In 1978, Federal law authorized a fourth judgeship for South Dakota. Kornmann was a candidate, but President Jimmy Carter chose South Dakota Supreme Court Justice Donald Porter.

Two years later, Kornmann got the nod from Carter for the position being vacated by Judge Nichol. Seeing the writing on the wall of Carter’s likely 1980 loss to Ronald Reagan, however, Kornmann withdrew his name. A year later, President Reagan appointed John Jones.

Almost a decade and a half later, with the charm of the third time, he became the thirteenth federal judge in South Dakota history. It began with a call from Judge Jones who first thanked him for his gracious withdrawal in 1980 (an amused Kornmann notes the grace was easy since he had known he wouldn’t get confirmed that close to a Presidential election). Then Jones explained that he would be taking senior status at the end of 1994 and suggested Kornmann call Senator Tom Daschle to initiate FBI and American Bar Association investigations of his background. Daschle also enlisted support from Republican Senator Larry Pressler and Democratic Representative Tim Johnson. On January 23, 1995, President Bill Clinton nominated him. During his Senate confirmation hearing, Kornmann says committee chair Republican Senator Mike De Wine of Ohio “noted that I was the first one-time Capitol Policeman to be nominated for such a position and stated that he was pleased to offer his support.”

On March 24, Daschle called Kornmann, saying, “Your number is 38. I said, ‘What does that mean?’” When he watched the proceedings on C-Span, “Majority Leader Senator Bob Dole moved to confirm nominees 34, 35, 36, and 38, and the number system thus became clear to me.” Unanimously confirmed by the Senate, he took the oath of office and was installed May 7, 1995. He observed that the timing from nomination to confirmation “was almost a record.”

Making a Federal Case of It

Kornmann was first based in Pierre for about a year and a half until he shifted to Aberdeen. His caseload, between Pierre and Aberdeen, was heavy. “At one time, I had the third highest criminal caseload of any federal judge in the country,” he remembers. Fortunately, he received help from South Dakota, North Dakota, Minnesota, and Arkansas judges.

Those criminal cases often involved FBI agents, whose policy prevented recording statements from defendants or others. “I pointed out to them that South Dakota sheriffs, highway patrol officers, and local police all often tape record or video tape statements, especially by the suspect or defendant,” he recalls. Instead, FBI agents wrote what the defendant allegedly said, which the defendant often disputed. “I told the U.S. Attorney that unless the FBI policy changed, I would start telling juries about these problems,” he said, and at the next trial, he instructed the jury that neither they nor he were present when the statement was taken and couldn’t know which version was correct. That defendant was found not guilty, and the FBI started offering to video tape suspects’ statements.

Kornmann speaks of several memorable civil cases. He ruled Federal Beef Checkoff to be unconstitutional. It took a dollar from every beef transaction to promote American beef, but the “Beef, it’s what’s for dinner” ads promoted all beef, American or not, so he struck it down. His decision was affirmed by the Court of Appeals, but the U.S. Supreme Court reversed him, holding that it was government speech that only Congress could stop. “I still think they were wrong,” he says.

On the day before South Dakota’s 2022 primary election, he mentioned a few cases that may have foreshadowed 2022’s defeated Amendment C. He struck down as unconstitutional a state law “severely regulating the gathering of petitions for constitutional amendments and referrals of acts passed by the legislature.” Last year, he also found that South Dakota’s deadline for filing initiated laws—twelve months before the election—was unconstitutional and restored the previous deadline of six months. The Court of Appeals let the first decision stand, but the second is on appeal. In addition, he struck down another state law that prevented nonresidents from contributing to ballot issue campaigns. While his wasn’t a ballot issue election, the victorious Representative Dusty Johnson criticized out-of-state money supporting his primary opponent.

What’s Next?

Judge Kornmann took senior status in 2008, but he continues to carry a full caseload, presiding over all federal cases in Aberdeen. He has also tried cases in Phoenix, Minneapolis, St. Louis, Connecticut, and New York state, as well as Rapid City and Pierre. He could have retired in 2008 and received full pay for the rest of his life, but he didn’t “because I’m grateful to the many federal judges who had come to help me when I had such a heavy caseload.”

But what happens when he fully retires? “Aberdeen absolutely will not get a judge again, not one that lives in Aberdeen,” he believes. Where the judge lives is up to the judge. Kornmann hopes Aberdeen remains attractive.

The Court House building’s profile has changed over time. Once fully occupied, most agencies crossed the street when the new Federal Building opened in 1974. In 1976 a new main post office facility opened on South Fifth Street, with a downtown location hanging on for another few decades until it closed in 2011. Now the only tenant is the Federal Court.

The building has also been sold multiple times in recent years, with a spotty record of landlord attention. The City of Aberdeen tried to buy the building in 2006, but the bidding went too high, and a private investor bought it from the General Services Administration. The city later acquired it through eminent domain and sold it to the Aberdeen Development Corporation. It is now privately owned.

Still, the judge argues the Court benefits Aberdeen. It has a $1 million payroll with eight local staff members. In addition, trials bring people to town, including court officers, but also attorneys, plaintiffs, defendants, victims, and families. The magistrate judge also comes for initial hearings and to appoint public defenders. All these people spend money in Aberdeen hotels and restaurants.

Kornmann hopes the building remains a Federal Court. He hopes the city sees the value of the Court’s presence here. Besides the impact of federal trials on the local economy, there’s something more there. Questions of federal, state, and tribal law are argued there—Constitutional issues. Behind those sadly bricked-up windows, arguments linking to the founding of the republic are adjudicated. Maybe there’s more to use and enjoy—and appreciate—than we think. //