Homesteads, Railroads, and Change in Brown County’s first city

In 1862, the Homestead Act was passed into law by Congress, opening up more than 270 million acres of public land to anyone, including women and immigrants, who had applied for citizenship, who had not taken up arms against the U.S. Government. The deal was simple; find the 160 acres of land you wanted, stake it out, file a claim, put up a structure, and it was yours free of charge. In all, 1.6 million homesteaders received free land, most of which was located west of the Mississippi River. At the time of the establishment of this act, Chief Drifting Goose still controlled the James River Valley, and those who would venture in were persuaded to leave. Because of this, the James River Valley in what is now Brown County stayed void of settlement until the fall of 1878, when Drifting Goose and his people were escorted back to the Crow Creek Reservation by troops from Fort Thompson. After that, settlers started to slowly move in.

Claiming the first settlement

On June 15, 1879, with Drifting Goose now living on the Crow Creek Reservation, a man by the name of Byron M. Smith brought a group of settlers from Minneapolis to settle at the junction of the Elm and James Rivers. He also personally brought in wagon loads of lumber and supplies to build a store. Mr. Smith was financially backed with “scrip” issued for the Lake Pepin Reserve in Minnesota, which he had obtained with the assistance of his friend, J.B. Bottineau, who was a Minnesota notary public.

When they arrived at their chosen spot, they discovered that a group of men from Spencer, Iowa, had already laid claim to the area and were building a dam. With his financial backers, Smith proceeded to buy the rights to the land from the Iowans for $1,700. He then, along with John Brigham, Melvin Baldwin, Martin James, and William Townsend, recorded the first official land deeds of what was to become Brown County. This also became the first settlement in the county, and as a result, others began moving into the James River Valley to stake claims.

Twelve days after Smith and his group arrived, on June 27, 1879, President Rutherford B. Hayes created the Drifting Goose Reservation in southern Brown and northern Spink counties. By fall, Drifting Goose had returned with 104 of his people, only to find the area occupied by settlers who were living in the cabins he had built and refusing to leave. Initially he camped near them, but as winter came he moved his people closer to Sisseton. During this winter of 1879-1880, Drifting Goose visited with government agents in Washington D.C., about the situation, but realizing the government would do nothing to remove the settlers on his reservation, he knew his homeland was gone forever. He negotiated with President Hayes to give up his land for additional supplies. On July 13, 1880, President Hayes revoked the reservation designation and Drifting Goose returned to Crow Creek, where he lived until his death in 1909.

After Drifting Goose had left for good, homesteaders flocked to the area. Soon, in addition to the five land deeds recorded by Smith and friends mentioned previously, nine more were recorded, totaling 14 deeds laying claim to 600 acres at this site. In November of 1879, the Richmond Township Company was formed by the new arrivals, and Smith and the others sold their land holdings to this company for $20,000. That was a huge sum of money for the time. In today’s economy, it would be equivalent to $460,000! With the purchase, the town was named Richmond after the newly formed company. Shortly thereafter, they applied for approval of being a post office site. At the time, a stage postal route had been established from Firesteel (north of current day Isabel) to Jamestown through Columbia. In the application, the town name was changed to Columbia, after the highly popular patriotic song of the time called “Hail Columbia.” John B. James was recognized as the first postmaster of Columbia, but not officially until post office status was granted on February 12, 1880. The site of Yorkville was also designated as a post office at this time.

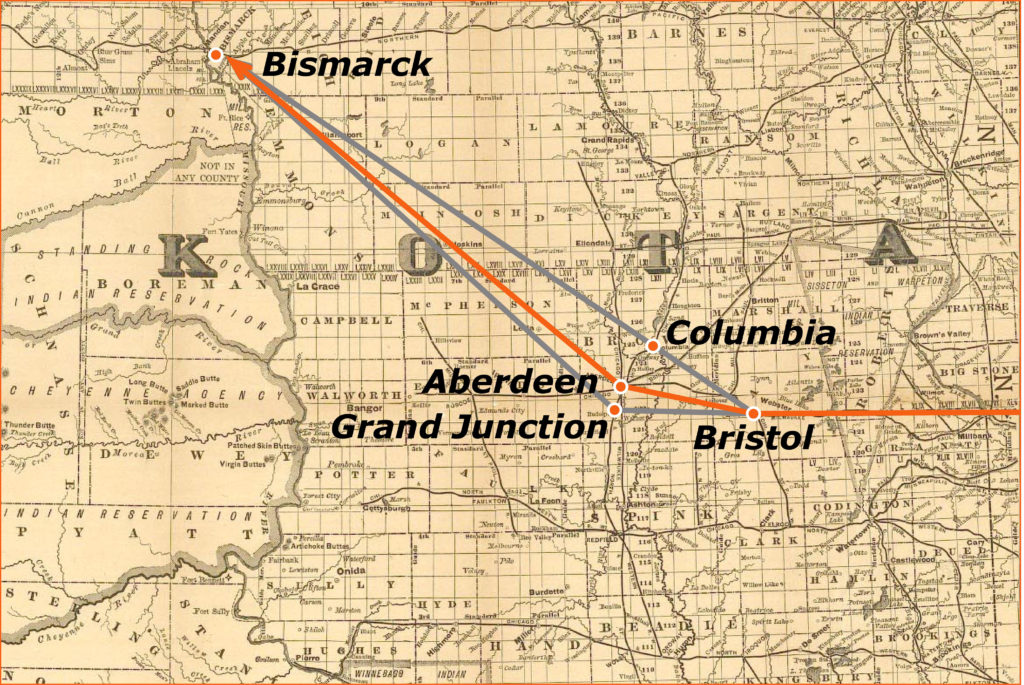

A Grand Plan to Win The Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Pacific Railroad (Milwaukee Road) was rapidly laying tracks west from Ortonville into the area of South Dakota in 1879 (shown in orange). They wanted to connect Bristol with Columbia as they intended to head northwest toward Bismarck. Due to Columbia’s expensive demands for right-of-way, the railroad bypassed Columbia. A competing railroad, the Chicago and North Western was heading north and a settlement popped up called Grand Crossing in anticipation of the Milwaukee Road intersecting at that point. The Milwaukee Road superintendent diverted the plans and angled the line a mile or two north of Grand Crossing to an unclaimed area, filed a land claim under his own name, bought a bunch of land in a slough, and called it Aberdeen. Buildings already built in Grand Crossing were moved up to Aberdeen. Grand Crossing vanished instantly, Columbia was severely handicapped.

The Arrival of the Railroad

With the railroads now moving rapidly east from Watertown, and Drifting Goose and his people gone, Columbia was betting that their growing town where the two waterways met would service the main rail lines to the west and become a railroad hub. Settlers believed in that “bet” too, and continued to arrive hoping to cash in on the impending economic boom. The railroads fueled this belief by telling Columbia they indeed wanted them to be the main railroad crossing point on the James River.

Two of the many new settlers to Columbia were William H. Wood and B.H. Randall, who brought with them a good number of wagons loaded with lumber and supplies to build the Howland Hotel. With the hotel construction in progress, the owner and hotel namesake, Mr. Howland, arrived in May of 1880 with supplies to finish and operate the hotel. However, the spring of 1880 was exceedingly wet, and as a result, many residents became ill. On June 2, 1880, Mrs. Howland arrived with the family’s two-year-old son, Henry. The hotel was nowhere near complete, and not suitable for housing, so a very crude shanty was erected to house them which provided little shelter from the continuous rains. Little Henry became ill and died within two weeks of their arrival. He was the first recorded death in what was to become Brown County.

Brown County was organized in Columbia on September 14, 1880. Afterwards, things moved rapidly for the next two years. In 1882, the dam that the original homesteaders from Iowa had begun building in 1879 was completed on the James River, creating Lake Columbia. On the dam, a three-story flour mill was built using the dam water releases for power. There were also four churches in the town.

In 1881, the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Pacific Railroad (often referred to as the Milwaukee Road) was knocking on Columbia’s door. They wanted to cross the James there with a line coming from Bristol. The Townsite Company of Columbia knew the Milwaukee Road was a big dog in railroad systems, and that if they came through Columbia so would the others, so they got greedy. They told the Milwaukee Road they would need a right-of-way payment and the construction of a draw bridge to accommodate the growing river boat traffic. The Milwaukee Road said no thanks. They decided to build the line further south, through what is now Aberdeen.

As a result, railroad lines built in 1881 to 1883 were as follows: The Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Pacific Railroad built a line in 1881 from Bristol to Groton to Bath to Aberdeen, another line in 1881 from Ashton to Warner to Aberdeen to Westport to Fredrick to Ellendale, and a line in 1883 from Aberdeen to Mina to Ipswich.

The Chicago and North Western (also known as Dakota Central) Railroad built a line in 1881 from Ordway Junction in Beadle County to Mansfield to Warner to Aberdeen to Ordway, and a line in 1882 from Ordway to Columbia. As you can see, four lines ran to or through Aberdeen, and only one went to Columbia. Aberdeen was thus created as the Hub City, but that’s another story.

The City of Columbia

Despite the decision by the railroads to build to the south, the city of Columbia was still growing, as people believed that the prosperity and growth of this city could not be overlooked. By 1883, two steamer boats were moving goods and passengers on the James River from Columbia north to Jamestown. They were named the Nettie Baldwin and the Fannie L. Peck. Sailboats and yachts also began appearing on Lake Columbia. The town contained four banks, two general stores, a courthouse, a school taught by their first teacher, George B. Daly, a railroad roundhouse and turntable in anticipation of becoming the fast advancing railroad hub, a grocery store, the four-story Grand Hotel, a meat market, a drug store, a dray service, two jewelry stores, a men’s clothing/furnishing store, a machinery business, several saloons, several rooming houses, a novelty store, a grocery store, a number of blacksmith shops, two doctors, four lawyers, a newspaper called the Columbia Sentinel published by C.E. Baldwin, and the Columbia Business College created by Professor Hildebrandt. Columbia was also the county seat, and the county fairgrounds and race track were built to the north and east of town. It was a huge trade center, attracting business from a radius of 40 miles from the city in all directions.

The town thrived for a few more years, but then things turned tough in a hurry. Communities along the railroad routes that were constructed between 1881 and 1883, that all but excluded the city of Columbia, began flourishing in their own rights, taking business away from Columbia. Other towns that were cropping up during this time, many created by railroad townsite companies, were Yorkville, Rondell, Bath, Detroit, Dodge, Huffton, Gem, Shelby, Merna, Lansing, Pectoria, Brainard, Liberty, Santa Clara, Chatham, Savo, Moody, and Bern.

By 1886, the railroad routes expanded again as follows: The Chicago and North Western Railroad built a line in 1886 from Columbia to Houghton to Hecla to Oakes, North Dakota, giving the city of Columbia a small ray of hope, and in 1887 built a line to the south from Verdon to Ferney to Groton. The Great Northern Railroad (previously known as the St. Paul, Minneapolis, and Manitoba) built a line in 1886 from North Dakota to Claremont to Huffton to Putney to Plana to Aberdeen, completely shutting Columbia out.

In 1887, Columbia lost the county seat to Aberdeen, and river shipping was abandoned by most for railroad shipping. Panic spread as people and businesses scrambled to minimize their losses. Entire city blocks of this once sprawling, growing town literally disappeared. Businesses, buildings, and homes were either moved elsewhere, or dismantled for materials. The once magnificent courthouse was used as a school by the remaining residents until 1910.

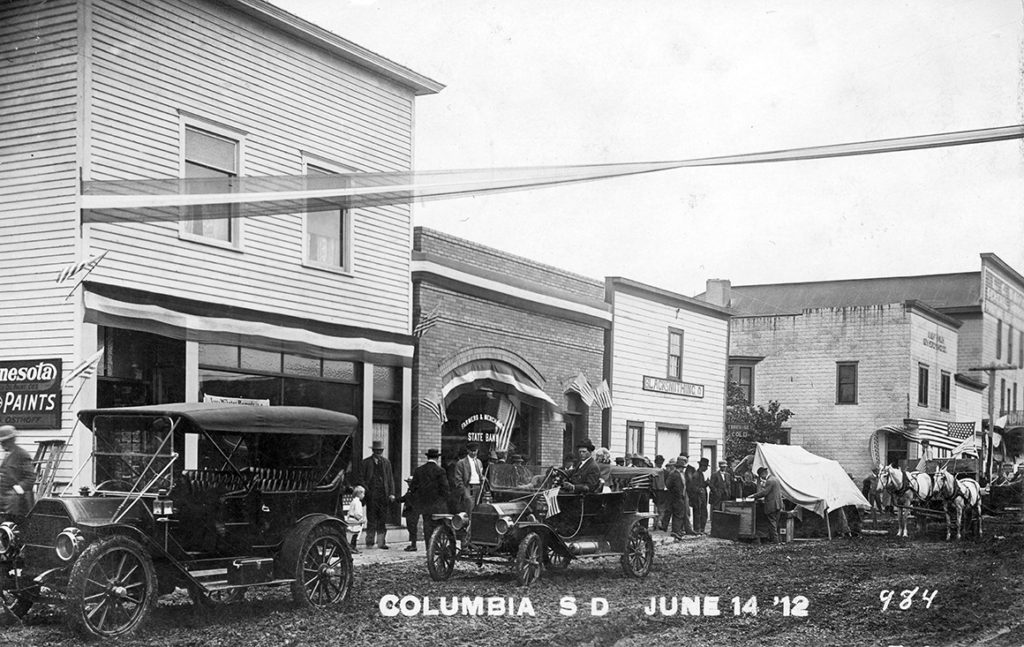

The use of automobiles further assisted in Columbia’s demise. Travel to other towns, particularly to Aberdeen for needed goods, led to more businesses closing. This, coupled with numerous drought years resulting in major crop failure, added to the population exodus. Several large fires also took a heavy toll on Columbia. Two in particular stand out. A fire that occurred in 1914 took out a full city block that included the courthouse, a hotel, a mercantile, a hardware store, and several other businesses, leaving nothing but ashes and rubble.

The final nail was the fire in 1925 that destroyed four farmer’s elevators and the depot. Area farmers who could not settle their debts, as well as other men of means and businessmen, just disappeared overnight, leaving the community with a bonded debt of close to $14,000, which was not retired for many years.

Over the years businesses and families have come and gone, leaving the city of Columbia the small and quiet town we know and love today. // – Mike McCafferty

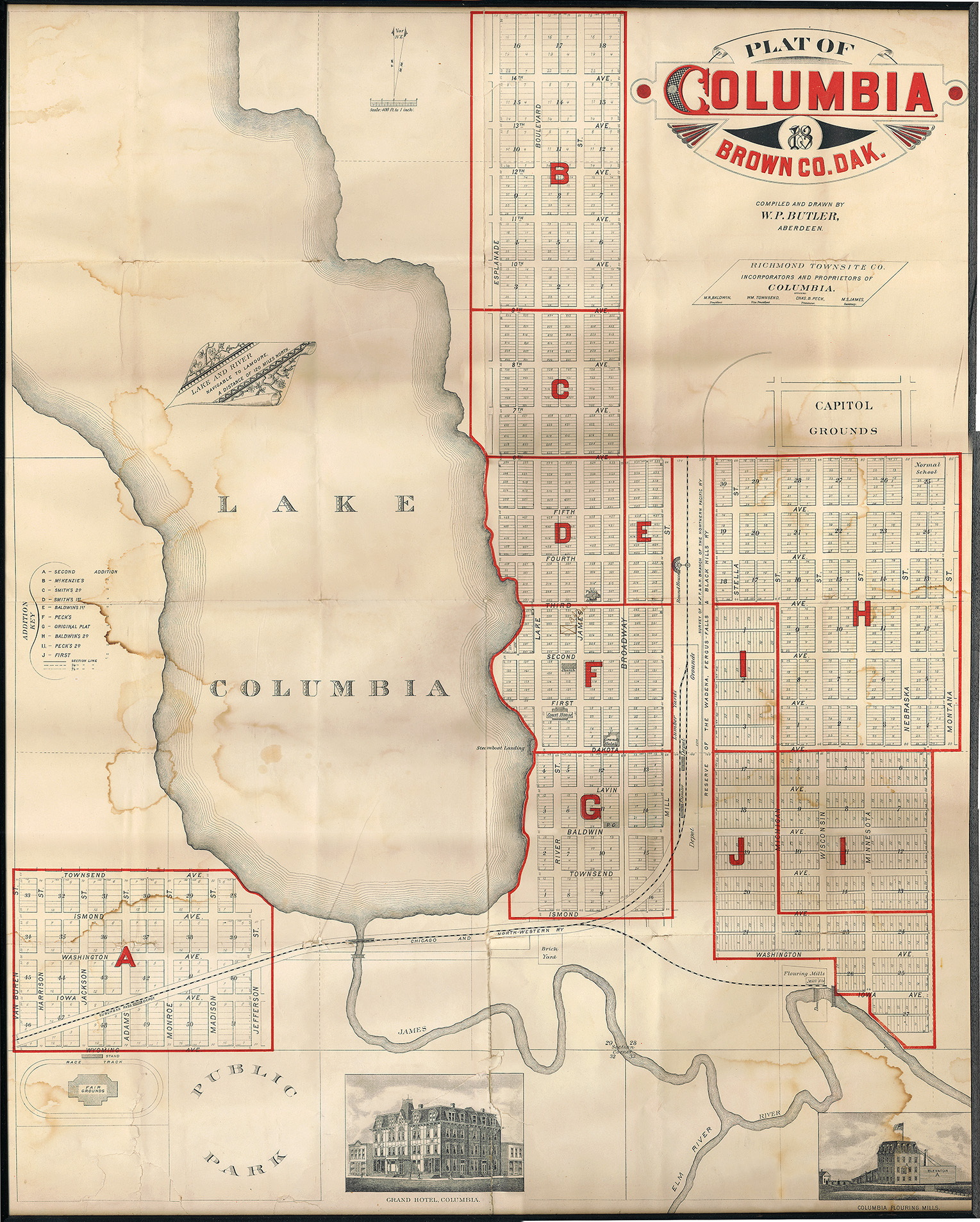

A vision that never happened This 1883 map of Columbia was probably a combination of what was already on the ground and what was planned for the future. Economic and physical disasters pretty much thwarted this vision, ending Columbia’s plan to be a capital city. As you may know, there is no lake there now, but there was. Many stories exist of the riverboats mooring there on their journey up and down the James River. It’s interesting to note that this map was drawn by an interesting fellow named W.P. Butler. He was one of the first mapmakers to draw all the railroad lines emanating from Aberdeen, and thusly defining it as the Hub City. He came to Aberdeen in 1881, as things were just getting started. There is a complete story about him in Don Artz’s book, A Souvenir of Aberdeen The Railroad Hub of the Dakotas. The late Mr. Artz writes in his dedication to Butler, “…Walter Percy Butler deserves to be remembered as the man who put the Hub City on the map.”