One of the most famous residents of Spink County lived there about 16 years before the county was created, but only for a few days and against her will. Nonetheless, Abbie Gardner was a looming figure in the imagination of my youth in Redfield. That said, until I learned her story recently, her name wasn’t much more than a marker on the highway. How we remember history is interesting.

One of three historical markers in a small roadside park on Highway 281 two miles north of Redfield frames the story: “About one mile east of this spot Abbie Gardner was delivered to her rescuers on May 30, 1857 after eighty three days of captivity among the Sioux Indians following the Spirit Lake massacre in Iowa.” Like any frame, this summary crops out factors such as what preceded and followed the event. This article expands that picture.

Abbie Gardner

Looking for opportunity, Abbie’s father Rowland moved his family west from New York, arriving in northern Iowa in the summer of 1856. He built a home on Lake Okoboji, near Spirit Lake, for his three-generation family of nine, including three adolescents and an infant. They were the first white people to settle in the area.

The land was unsettled, but not unoccupied. Native Americans still lived there searching for scarce resources. In her memoir published 30 years later, Abbie writes favorably of some area tribes but not one particular group. In her florid nineteenth-century style, she asserted, “no other tribe of aborigines has ever exhibited more savage ferocity or so appalled and sickened the soul of humanity by wholesale slaughtering of the white race as has the Sioux.”

On the morning of March 8, 1857, when Abbie was 13, the Gardners gave a small band of Wahpekute Dakota Sioux some food. The Native Americans harassed the family, even brandishing a gun, but then left. A few tense hours later, Rowland spotted nine warriors coming and announced, “we are all doomed to die.” The Native Americans entered, led by their chief, Inkpaduta, about whom Abbie remembered, “He was deeply pitted by smallpox, giving him a revolting appearance.”

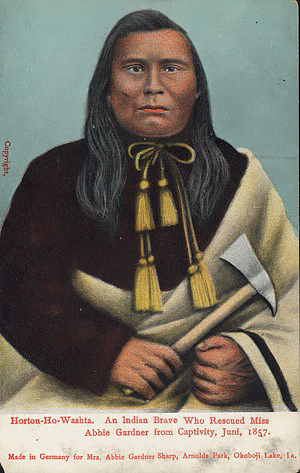

Inkpaduta

About 60 at the time of the massacre, the chief was a man with a past, if not likely all that was ascribed to him in later years. Perhaps the most visible mark of Inkpaduta’s history was the smallpox that revolted Abbie. An epidemic twenty years earlier had killed more than half of his band. Of course, smallpox didn’t exist in America before the arrival of Europeans.

In an 1851 treaty, some Dakota bands traded land for a reservation and supplies. Poor conditions on the reservation, often due to incompetence and corruption, meant little actual sustenance, however. The remaining Dakota Sioux, including Inkpaduta, who had not signed the treaty, searched for food on the prairie instead.

A few years before the massacre, Inkpaduta moved his people into the village of his relative Sintominiduta. In 1854, a white man—a whiskey trader and horse thief—killed the chief. Inkpaduta reported the murder, and authorities indicted the man but did little to catch him. Adding insult, the prosecutor mocked the death, nailing Sintominiduta’s head to a pole.

In the brutal winter of 1856-1857, deep snow and deeper temperatures plagued Inkpaduta’s people, but they were able to camp near a friendly white farmer’s home dozens of miles south of Spirit Lake. The whites grew tired of sharing resources, however, and in February, they wrecked the Native Americans’ camp, seized their weapons, and expelled them, ignoring Inkpaduta’s protests that they would die without hunting weapons. Watching his grandchild die of exposure and starvation, Inkpaduta moved north, stealing food and guns.

Massacre, Captivity, and Release

Just a few weeks later, when Inkpaduta’s men returned to the Gardner house in the afternoon of March 8, they demanded more food. “As father turned to get them what remained of our scanty store,” Abbie wrote, “they shot him through the heart.” Then followed the brutal murders of the rest of the household. Except for Abbie, who was taken with the band.

Altogether, over about two weeks, Inkpaduta’s people killed more than three dozen settlers around Spirit Lake and southern Minnesota Territory. The Native Americans also took another three women captive and escaped from pursuing militia.

The band generally moved northwest from the scene of the massacre. Over nearly three months, the Native Americans murdered two of the captives, one in the Big Sioux River near Flandreau because her illness slowed the group and the other perhaps near Spink County for refusing the demands of Inkpaduta’s son. This occurred not long after she and Abbie had been sold to a Yankton Sioux and not long before Abbie was released. In between the deaths, two Sioux brothers from Minnesota purchased the other captive and took her to whites in Minnesota.

Now the only remaining captive, Abbie walked with the group through what would become Brookings, Hamlin, and Clark counties until they reached Spink. Abbie wrote, “the scene was really sublime. Look in any direction, and the grassy plain was bounded only by the horizon. … This was repeated day after day till it seemed as if we were in another world. I almost despaired of ever seeing a tree again.”

The band reached the James River a few miles northeast of Redfield—about 200 miles and 80 days from Spirit Lake—where several hundred Yankton Sioux were camped. Her captor let people into his tepee to see perhaps the first white person they had ever encountered, and Abbie wrote the visitors included “three Indians dressed in coats and white shirts, with starched bosoms.” They were on a mission to ransom her.

After three days of negotiations, Abbie was released in exchange for “two horses, twelve blankets, two kegs of powder, twenty pounds of tobacco, thirty-two yards of blue squaw cloth, thirty-seven and a half yards of calico and ribbon, and other small articles.” Her new purchasers received her near the confluence of the James River and Turtle Creek and took her to Minnesota’s governor.

Remembering

The story began to be told immediately. Newspapers reported rumors that exaggerated everything—the size of Inkpaduta’s group, the alleged burning of Mankato, rampant rape and mutilation—which prompted retaliation against innocent Dakotas. Pamphlets, short books, and newspapers reported similarly on the story over coming decades.

In 1885, Abbie published The Spirit Lake Massacre and Captivity of Miss Abbie Gardner (authored as Abbie Gardner Sharp); several editions and reprintings followed. Not surprisingly, it is filled with fear and hate for her captors, but it has moments of seemingly objective descriptions of their life on the prairie.

Monuments memorializing the events also began to appear, starting in Iowa. Abbie bought the home where her family was killed, and in 1895, it was dedicated as a historical monument. The Abbie Gardner Cabin and Museum in Arnolds Park, Iowa, remains open as a tourist attraction.

The remembering came to South Dakota, too. In 1918, the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) announced plans to “mark all historic places in the state,” including the rescues of the two captives. A 1924 Aberdeen newspaper described a “picnic and regular meeting of the Charlotte Warrington Turner Chapter DAR at Hagmans grove near Redfield.” This was across Turtle Creek from the presumed site of Abbie’s rescue. In the summer of 1927, they dedicated a marker on that spot. From a pasture, the three-foot tall granite and stone pyramid still overlooks the merging streams, but its historical plaque is gone. Mary Lou Schwartz, my high school librarian and director of Redfield’s C&NW Railroad Depot, took me to the site, along with fellow Spink County Historical Society member Alan Maddox, my former scout leader.

On August 15, 1929, the Redfield DAR chapter, plus those from Pierre, Mellette, Ashton, and Aberdeen, as well as the former state historian, Doane Robinson, dedicated the larger stone marker on Highway 281, which is quoted at the beginning of this story. The Abbie Gardner Sharp Girl Reserves (a YWCA affiliate group) of Mellette also attended. The group’s name, as well as Abbie Gardner appearing as a character in a Women’s Achievement Day skit years later, are interesting ways of remembering a girl with a very brief county residency three quarters of a century earlier.

In a 1963 story about a Sisseton event remembering the Native Americans involved in Abbie’s rescue, a reporter hyperventilated, “The ringleading bad guy in this episode was Inkpaduta—a name that has made many a South Dakota grade school boy grind his teeth with rage as he read his history book.” Not this schoolboy. Even in the school closest to the scene of Abbie’s return, her story didn’t make it into my history books or classes.

But it did make the lunchroom wall. When a mural in a Redfield store depicting her rescue was covered in a remodeling, the Redfield High School Pheasant Call reported, “many people felt that it was regrettable that it should be ‘lost’ to our community.” So the 1962 art class recreated it in the school lunchroom. Today the mural is in the Spink County Museum, rescued from the school’s demolition a few years ago.

Aftermath

For decades, the perception of the Spirit Lake Massacre featured the one-dimensional view of Inkpaduta as a man who simply hated whites. Despite his occasional good relations with them—one settler asked him to watch over his family when he traveled on business—he was long remembered as a savage outlaw. In 2008, Paul N. Beck’s Inkpaduta: Dakota Leader unraveled previous understandings that relied almost exclusively and uncritically on reports of whites. Hardly exonerating the chief but situating him in the context of violence on the Plains, Beck concluded, “besides the Spirit Lake massacre, little solid evidence exists for this demonization.” He suggests Inkpaduta was a hero to Sioux for fighting for land and tradition, but a bogeyman to whites because he was never caught, punished, or defeated in battle and never forced onto a reservation.

After the massacre, he moved around the area, pursued by whites as well as Native Americans motivated by the denial of government benefits until his capture. Inkpaduta fought in battles with the U.S. Army, including the Little Bighorn in 1876 (Black Elk noted his presence). In the end, he fled to Canada with Sitting Bull and died there in 1881, far from where he had once tried to live.

After her release, Abbie reunited with her sister Eliza, who was not home at the time of the massacre. She also connected with the families of the murdered captives, in fact, marrying one of their cousins just two months after her release. Hers was not an easy life. In the 2015 reprinting of her book, the publisher asserted, “It seems fair to conclude that much of Gardner’s long history of illness after the event was due to what we today call post-traumatic stress disorder.”

In the time between the initial writing of her book and a postscript she added to the 1912 edition called “An Epoch of Advancement,” Abbie seems to have found some new understanding of Native Americans (perhaps primarily Christian Native Americans). In 1892, she searched for the Native Americans who had rescued her and revisited places her captors had taken her (although apparently not Spink County). In Flandreau, she spoke to the Native American congregation at church:

I assured those present that notwithstanding all that I had suffered I entertained nothing but the kindest regard toward the race which had exterminated everything in the world dear to me; that through the revelation of the spirit of the Savior I had overcome my former spirit of hatred toward the Indians; and that I entertained only good wishes for their advancement in every possible way.

Abbie died in 1921 and is buried with her family at the Lake Okoboji cabin.

***

In an era when how we remember history is often called into question and the uses to which history and some historical symbols are put can be questionable, such as in the case of Confederate monuments, the markers in Spink County seem refreshingly modest in their aspirations. While they do leave out the broader context, in their simplicity (there are no depictions of heroes or villains), they seem more to point to events and places rather than to convey blunt ideological messages. It’s also notable that the markers indicate an apparent attempt at balance in remembering both Abbie Gardner and Council Rock (see “Council Rock” sidebar)—representing the competing cultures of the Plains. Though some will argue the monuments simply advance a narrative of the decline of savagery and advance of white civilization.

Just as the markers merely point to history, this article only slightly widens the frame. We can’t gloss over the brutality of the violence inflicted on Abbie’s people any more than we can ignore the disastrous effects of “civilization” on the people who were already living there. History is messy. The wider picture often isn’t pretty, but even if it’s disagreeable, it needs to be seen, understood, and argued—not silenced. //

- Abbie Gardner, in the photo on the cover of her memoir about her experiences of the Spirit Lake Massacre, first published in 1885.

- The modern layout of the 1929 roadside marker. Photo by Patrick Gallagher.

- Presumed to be the only known photograph of Dakota chief Inkpaduta who led the attack in the Spirit Lake Massacre.

- Hotonhowashta, also known as John Other Day, was one of the Native Americans who rescued Abbie Gardner. He became a hero to Whites for his help in the 1862 Sioux Uprising in Minnesota.

- The 1927 pyramidal monument marking the location understood to be where Abbie Gardner was released to her Native American rescuers still stands in a pasture above the confluence of the James River and Turtle Creek northeast of Redfield. Photo by Patrick Gallagher.

- Redfield High School students recreated a local mural depicting the release of Abbie Gardner on the school lunchroom wall. Photo by Patrick Gallagher.

- In 1929, the Daughters of the American Revolution dedicated the large stone roadside marker on what would become U.S. Highway 281, noting the nearby release of Abbie Gardner. Photo courtesy of Spink County Historical Society.

- Two miles north of Redfield on Highway 281, this roadside stop features three historical markers. Each convey very short stories of significant incidents that happened near the markers. Photo by Patrick Gallagher.

Council Rock

Next to the large stone monument on Highway 281 about Abbie’s release is one about Council Rock, a nearby gathering place for Sioux Native Americans of the Dakotas. Abbie doesn’t specifically mention Council Rock, but she was released in its general vicinity.

The 1975 Bicentennial marker describes the place:

The Sioux tribes established, near here, Council Rock as a central meeting place for all the bands. Using a black oviate [sic—presumably ovate] rock measuring 6” x 11” surrounded by a circle of stones 15 feet in diameter, representatives of each tribe sat with feet extended toward the Council Rock to settle affairs of the Sioux nation. The site had religious significance and was maintained as a sanctuary from war and strife. As many as 3,000 Teton, Santee, Yankton and Yanktonai gathered here annually for a great Trade Fair, where goods were bartered among the tribes. Needy persons could always find supplies here.

The original rock disappeared in 1892, but locals undertook efforts to remember it, creating replicas. In 1939, the DAR and county school children placed a monument to Council Rock east of Highway 281.

- A marker of the Council Rock site east of Highway 281. The newly placed stone simulates where the actual rock could have been placed. Photo by Patrick Gallagher.

- The Highway 281 historical marker for Council Rock. Photo by Patrick Gallagher.

- A recreation of the presumed layout of the Council Rock site near a Spink County school. Photo courtesy of South Dakota State Historical Society.