A half-century ago, the era of professional baseball in Aberdeen came to an end (not counting a brief reprise, itself ending a quarter-century ago, but more on that in a future issue). When they launched in 1946, the minor league Aberdeen Pheasants were all the rage at a time when Aberdonians were both ready to enjoy life after a world war and had the time—or at least fewer distractions—to see the national pastime in town.

This brief pastiche of the history of the Pheasants, the people involved, and the impact the team was guided by several sources, which are referenced in the text and/or in credits.

IN THE BIG INNING

The Northern League was a Class C minor league (AAA was the highest and D the lowest). Founded in 1933 and comprised of teams in the United States and Canada, the League ended a World War II hiatus and invited Aberdeen to join in 1946. A local committee quickly raised the $2,000 deposit needed to lock in a spot in the League then looked for a Major League team that would supply players.

The fledgling team’s board sent a delegation led by its president, Aberdeen florist Ben Siebrecht, to St. Louis to meet with the Browns organization. Dennis Maloney, a local attorney (now 92 years old) who took his attorney father’s place on the Pheasants board some six decades ago recalled that the Browns were known as “First in booze, first in shoes, and last in the American League.” Undaunted and bearing a load of Siebrecht’s roses, the Pheasant leaders cut a deal that survived the Browns’ move in 1953 to become the Baltimore Orioles. That agreement would become the longest working agreement between a major and minor league team in baseball history.

The board raised $20,000 in operating capital through an unusual approach in baseball financing—selling stock communitywide, rather than just to wealthy people. More than 75 years later, Maloney praised the founding board’s ability to raise operating capital but acknowledged, “There were always money problems.”

Despite that, Aberdeen native and historian Daryl Webb, author of “Keep Pro Baseball: The Aberdeen Pheasants Baseball Team, 1945-1971” in South Dakota History (2016), noted in an interview, “Historians tended to think the owners of minor league teams didn’t understand the business, but I found in Aberdeen that wasn’t the case. Not only did they understand the business, they saw the team as a community asset.”

On May 19, 1946, 2,000 people filed into Aberdeen’s Municipal Ball Park to attend the first game of the Aberdeen Pheasants, a name chosen through a local contest. It was the beginning of a beautiful relationship.

Unfortunately, the new attraction was marred at first by the polio epidemic, which prevented children from attending games. The teenage Maloney was the rare youngster admitted—not in but on the stadium, where he spotted foul balls and directed shaggers to retrieve them. “The team couldn’t afford to lose baseballs,” he explained.

The team had a great first few years, winning the league pennant in their second season with an 82-36 record and bringing in 90,156 fans, the team’s highest for any year. In the late 1940s, they hosted two of the four Northern League All Star Games played in Aberdeen throughout their existence. The league leader hosted the game and played against all stars from the rest of the league. Aberdeen won three of those games, in 1947, 1949, and 1964, losing only the 1961 game. After the 1964 All Star Game, seven Pheasants joined the league all-stars to defeat the Minnesota Twins in an exhibition game.

Speaking of exhibition games, also in 1964, the Orioles came to Aberdeen to play their Pheasants farm team, the only time a Major League team has played in South Dakota. Some 5,000 fans watched the home team make it a game but come up short, 6-3.

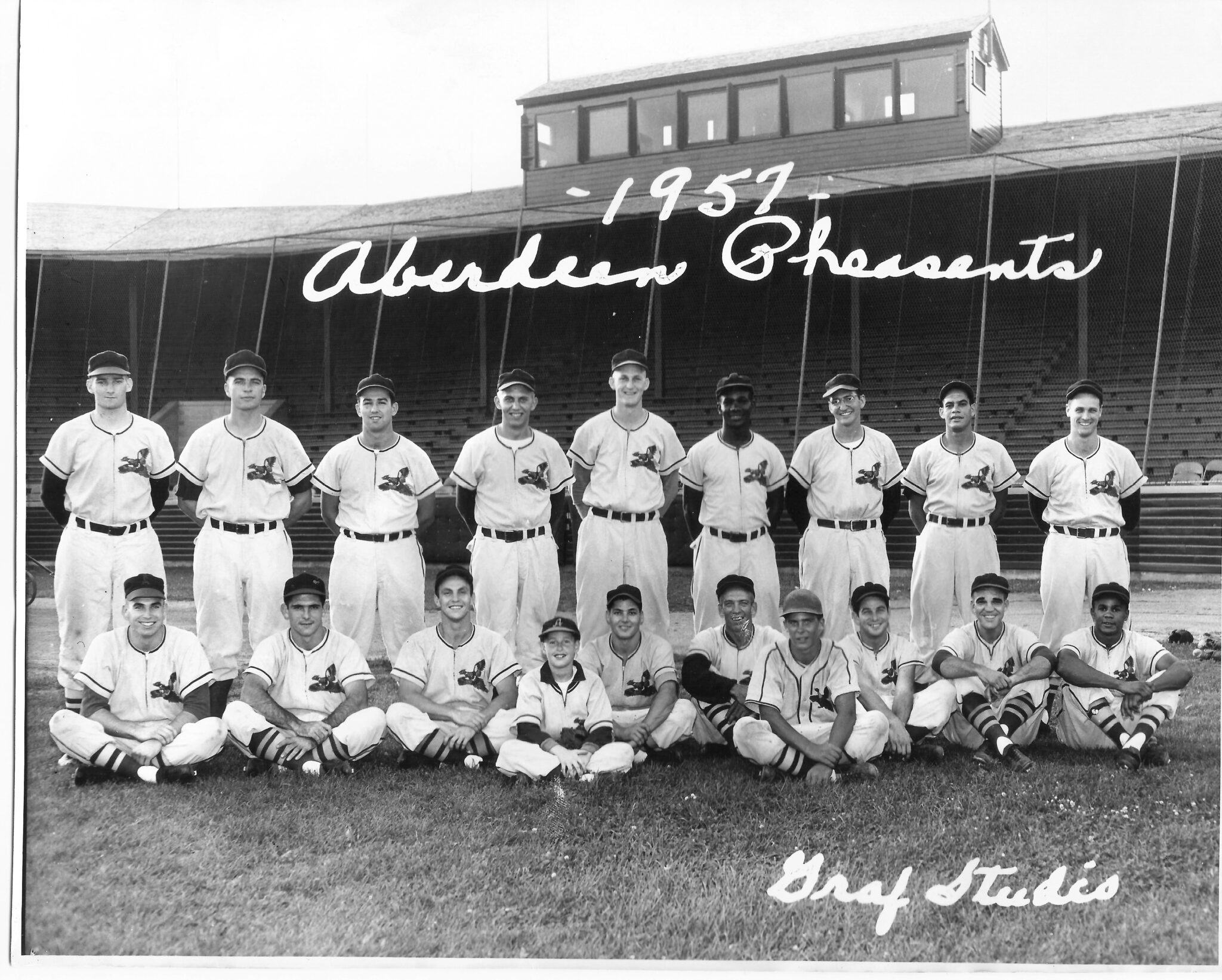

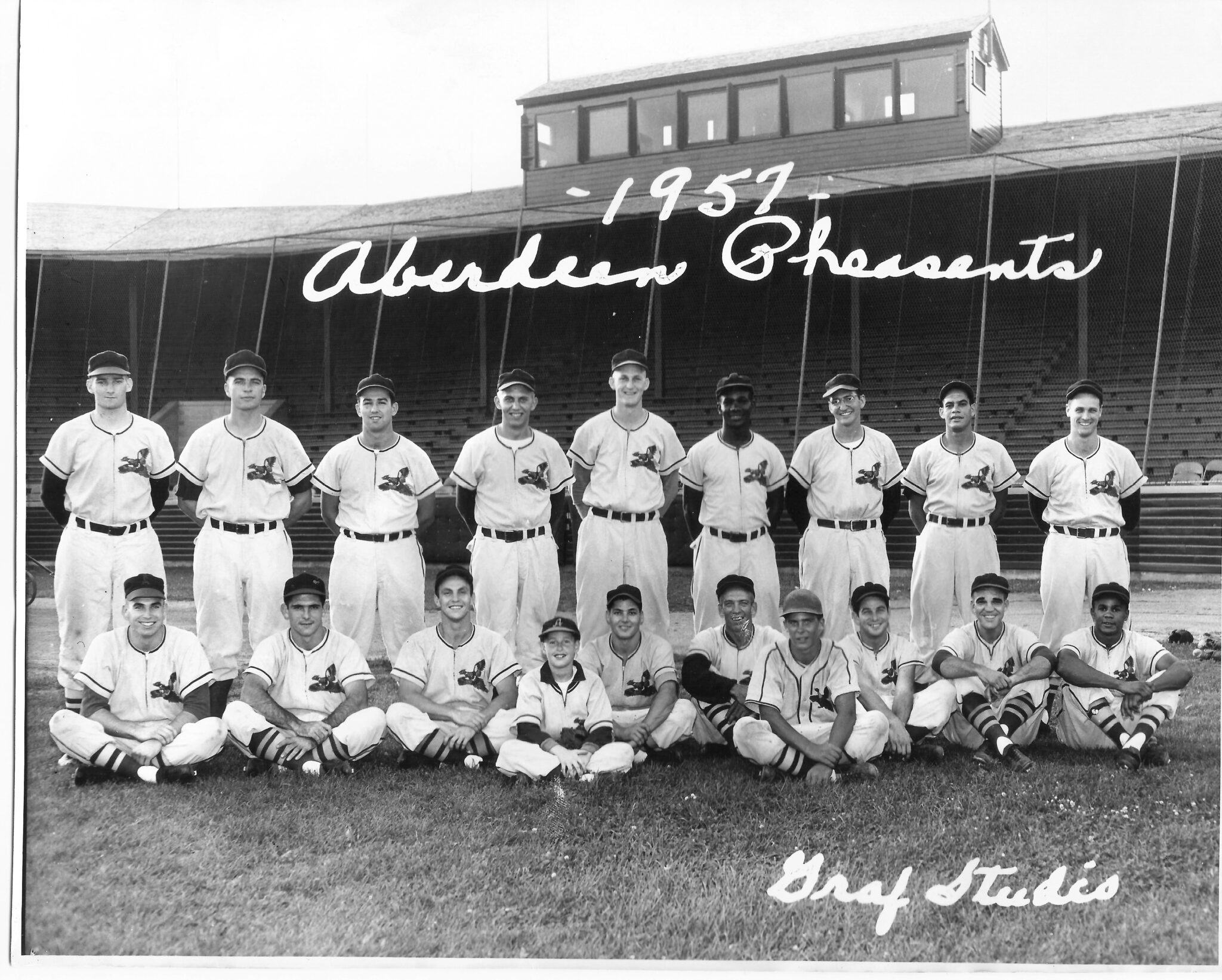

The Pheasants won the pennant—finishing first in the regular season standings—twice, in 1947 and 1964. The League had season-ending playoffs featuring the top four teams. The Pheasants lost the 1947 championship but won it in 1949, 1961, and 1964, defending that year’s pennant. The 1964 team was especially loaded, including such future MLB stars as Jim Palmer, Lou Piniella, Mark Belanger, Dave Leonhard, and Mike Fiore, among others. All told, in an indication of their overall quality, the Pheasants played in seven championship games and qualified for four other playoffs in the 16 years the playoffs were held when they were in the league.

IN THE STANDS

Aberdeen’s Municipal Ball Park was, according to Maloney, “the best ballpark in the United States for a minor league team.” Former Pheasants who wrote to local fan Ben Ernst (see sidebar) also said good things about the park. Built as a New Deal Works Progress Administration project in 1936 to serve youth and amateur baseball teams, it didn’t have lights until the Pheasants’ inaugural season was under way.

The stadium ably served the Hub City’s busy baseball scene until an August 1951 fire. The estimated $150,000 in damages included the grandstand, bleachers, and all of the Pheasants’ equipment, minus their road uniforms, which were at the cleaner. Local workers immediately began repairs, and games resumed there within weeks. About twenty years later, the City transferred ownership of the ballpark to Northern State University, where it was ultimately replaced by the Barnett Center.

Initally the ballpark saw good attendance for Pheasant games. In 1946-49, attendance averaged over 87,000. That was the high point, however, for both the Pheasants and minor league baseball as a whole. After drawing 40 million fans in 1949, attendance dropped to 10 million in 1963. Across the country, many teams folded, including several in the Northern League. The Pheasants’ attendance dropped by more than half between 1949 and 1962, from about 85,000 to about 39,000.

Declining attendance was partly due to weaker Pheasants teams, but there was also increased competition for fans’ leisure time in the 1950s. In Aberdeen, people had more access to golf, swimming, theater and other diversions. The biggest competitor, however, invaded fans’ homes: televsion. The Pheasants tried various promotions to attract fans, including a pony giveaway, which was Daryl Webb’s first baseball memory, and a home plate wedding, as well as a variety of community recognitions. Not surprisingly, fewer fans meant struggling finances, and the Pheasants board solicted donations to balance the books multiple times.

Eventually, the Orioles—and Major League Baseball—came to the rescue in the 1950s, at least in part. Maloney explained, “Originally the Pheasants organization paid everything for the team, including salaries, but it got too expensive for minor league teams to operate, so the Majors picked up the salaries.” The arrangement foreshadowed great things to come, at least for a while.

ON THE FIELD

One of fruits of that Orioles relationship was a bevy of talented ballplayers in Aberdeen. Despite occasional clunker teams, nearly 60 Pheasants made it to the bigs—and they include some of the biggest.

• Don Larsen, who as a Yankee threw the only perfect game in World Series history in 1956, wrote about arriving in Aberdeen unexpected in 1947 and sleeping in the Sherman Hotel lobby. He paid his way into the Pheasants game the next day and watched from the bleachers. Researching his Pheasants history article, Daryl Webb talked to an Aberdeen man who had watched Larsen’s World Series gem. He didn’t move the whole time, afraid of jinxing the perfect game.

• The 1958 Cy Young Award-winning Yankee “Bullet Bob” Turley won 23 games for the Pheasants and astonishingly pitched complete games in every one of his 28 appearances in the 1949 season.

• Tito Francona, a one-time All Star and all-time journeyman ballplayer, played for nine MLB teams in his career. He married an Aberdeen girl, and their son Terry, who was born in Aberdeen, became a two-time World Series champion manager, breaking the Red Sox curse of the Babe, and as Cleveland’s manager nearly breaking their curse—losing to the curse-breaking Cubs.

• “Mad Earl Weaver,” as Maloney called him, was a “wild man,” who “got kicked out of many games.” One of only two former Pheasants in the Baseball Hall of Fame, he is the fourth most ejected manager in MLB history. In 1970, the former Pheasants manager led the Orioles to a World Series championship over South Dakota native Sparky Anderson’s Cincinnati Reds.

• Cal Ripken, Sr. managed the stellar 1964 team and stayed with the Orioles organization for decades, coaching at the Major League level. His son Cal, the Orioles Hall of Fame shortstop who set the record for most consecutive games played, was an occasional batboy for the Pheasants. In a letter to Ernst, Dave Leonhard remembered Cal Jr.: “We considered him a pest, always wanting to play pepper with us, etc. Who knew?”

• Jim Palmer is the only Pheasant player in the Baseball Hall of Fame. During the Orioles exhibition game that season, Maloney remembered the Orioles manager saying of Palmer, “Put that kid on the airplane” to go back with them. In his book, Palmer recalled at his Hall of Fame induction being moved “by the number of people who introduced themselves and said they had come all the way from Aberdeen.”

• “Sweet Lou” Piniella played 20 games for the Pheasants in 1964 before being called up to the Orioles. He won American League Rookie of the Year, two World Series as a Yankee player and one as the Reds manager, three Manager of the Year awards, and he ranks 13th on the list of most-ejected managers.

• Future American League Rookie of the Year, All Star, and World Series champion Al Bumbry came to Aberdeen a star in the making. When Maloney asked him why he hadn’t been signed by the majors, Bumbry said he just gotten out of Vietnam. “Signing Bumbry is one of best memories from working with the Pheasants,” Maloney remembered.

And this list doesn’t include the future MLB stars from visiting teams who came to play in Aberdeen, such as Henry Aaron, Lou Brock, Steve Carlton, Ken Griffey, Sr., and that’s from just the first few letters of the alphabet.

IN THE END

In 1970, several Orioles executives came to Aberdeen in recognition of the 25th anniversary of their working agreement with the Pheasants. Webb noted the “very long relationship with the Orioles, which was uncommon in baseball.” But it couldn’t last forever.

After the Pheasants’ star-laden 1964 team, their fortunes, as well as those of the Northern League and much of the minor leagues, took a turn. An early 1960s reorganization made the League Class A, now the lowest level except for the rookie league. Then in 1965, it was reduced to rookie status, which affected the quality of the teams and therefore attendance and finances. The number of teams in the league declined until there were only two in early 1972. On top of these external forces, Maloney recalled that the City gave the ballpark to NSU in 1971, and the team would have had to find a new place to play in 1972.

Named president in late 1971, Maloney had the dubious honor of trying to prevent the team’s demise. He led a delegation to a November 1971 Northern League meeting with the goal of keeping it afloat, but by mid-January, first Duluth then Sioux Falls voted to bow out. With only Aberdeen and St. Cloud viable and efforts to add other teams failing, the League ceased operations. The Orioles then regretfully cut ties with the Pheasants, ending the longest-running minor league working agreement in baseball history.

More succinctly, Maloney recalled, “The team folded because the Majors concluded they couldn’t afford all the salaries for players all around the country, so they shut down the B and C league teams and moved them to Florida. The AAA and AA teams were kept, and that’s when the Northern League and Pheasants died.”

Despite the effective end of the team, the Pheasants paid the ballpark’s light bill in 1972. The legacy continued, as the team used their remaining assets to support baseball in Aberdeen for decades. As Maloney put it, “Baseball money was for baseball.”

The last comment epitomizes Webb’s observation that the team’s owners understood the Pheasants were more than just a business enterprise. In fact, virtually none of the investors expected a financial benefit from owning the team. What they knew was that their investment was paying dividends to Aberdeen as a whole, in entertainment value, revenue, and community pride.

It’s not surprising that big league sports hasn’t fully let go of Aberdeen, or vice versa. //

Philbert the Pheasant

Early in the Pheasants’ life, they gained a mascot. Gordon Haug, a window dresser for Olwin-Angell department store, drew a cartoon pheasant named Philbert, who appeared in the Aberdeen American News after each game to comment on the team. The cartoon became so emblematic the newspaper took to calling the team “Philbert.”

Daryl Webb reported coming across a suggestion that Philbert was the inspiration for Ollie the Oriole, the parent team’s mascot, created years after Philbert. Unable to verify the story, the reputable historian wouldn’t include it in his article, but it’s baseball: if the facts don’t fit, print the legend.

Daryl Webb

Aberdeen native Daryl Webb, then a history professor at Cardinal Stritch University in Milwaukee, said his first baseball memory was a Pheasants game when he was about five, in what was probably the team’s last season. “It was fan appreciation night when they gave away a pony,” he said. “They did that every year, probably the same pony.” The memory of the Pheasants lingered in town, he noted, and he did his part to preserve it, writing the article “Keep Pro Baseball: The Aberdeen Pheasants Baseball Team, 1945-1971” in South Dakota History (volume 46, number 2, 2016), a great overview of the team.

The article grew out of his work at Dacotah Prairie Museum, where he produced a display on the Pheasants in the early 1990s. It eventually became a larger exhibit, running 1998-2000. “I was the driving force for the exhibit,” he said. Working at the arts council at the time, he offered to design it. “I loved to work on it,” he said, adding, “I was especially happy that I got to do some of the research with my dad,” the late NSU history professor Robert Webb. The pair later presented their research at a history conference.

The Church of Baseball

Fans of the baseball movie Bull Durham may be unaware of Pheasant links. Writer-director Ron Shelton played in the Orioles farm system and briefly encountered former Pheasant Steve Dalkowski. With an alleged 105 mph fastball and control “issues,” “Dalko” threw a no-hitter for the Pheasants in which he struck out 21 and walked eight (control issues indeed). Shelton based the movie’s fast and wild pitcher “Nuke” LaLoosh partly on Dalko.

Shelton’s book on the making of the film, The Church of Baseball, also mentions former Pheasants and Orioles pitcher (and Jim Palmer’s Aberdeen roommate) Dave Leonhard, who had his own no-hitter for the Pheasants. The Johns Hopkins University graduate Leonhard might have inspired the movie’s line about a player once seen reading a book without pictures.

In another coincidence, the movie features an on-field wedding, and the Pheasants also hosted one at home plate before a 1953 game to draw in fans.

Ben Ernst

One of the biggest local Pheasant fans was born nearly two decades after their demise. In fact, Ben Ernst remembers that his first baseball game was a 1995 Pheasants game. But he heard the memories. “My grandpa was neighbors with the Ripkens,” Ernst said. “He remembered seeing Cal, Jr. playing catch as a kid.” Daryl Webb’s Dacotah Prairie Museum Pheasants exhibit also fostered his love of baseball.

Going to California after graduating from Central, he got a job with the Los Angeles Angels baseball team. In the first of many coincidences, the parents of his Angels’ boss were South Dakotans. “Out of all the teams getting a job on hope and a prayer, it had to be the Angels,” he joked. After he returned to Aberdeen, he found many connections between the Pheasants and Angels, including:

• Let go by Orioles and picked up by the Angels, former Pheasant pitcher Bo Belinsky threw the first major league no hitter in California history against the Orioles in 1962. Facing former Pheasant pitcher Steve Barber, he got former Pheasant slugger Dave Nicholson to make the final out. (Ernst found a celebrity magazine featuring photos of Belinsky with Gilligan’s Island’s Tina Louise and bombshell and South Dakota native Mamie Van Doren—not to be confused with an angel.)

• Don Heffner, Don Larsen’s 1947 Pheasants manager, was later an Angels coach.

• In 1961, the Angels’ first game as an expansion team was played at the old Baltimore Memorial Stadium with former Pheasant John Papa on the mound for the Orioles.

Scorecard of Sources

The Aberdeen American News reported extensively on the Pheasants, in particular sports reporter Larry Desautels.

The Dacotah Prairie Museum has a great collection of Pheasants (1946-71 and 1995-98[?]) artifacts.

Former Aberdonian David Trombley’s baseball history website–https://usfamily.net/web/trombleyd/ –contains volumes on the Northern League plus other baseball in and around South Dakota.

Aberdeen resident Tony Urbaniak’s “The 1947 Aberdeen (SD) Pheasants” in the Minor League History Journal is an enjoyable account of the Pheasants’ pennant-winning 1947 season with a look at much of the day-to-day aspects of minor league baseball, including the interesting number of forfeited games due to rules violations, often fights. The article is excerpted in Trombley’s website above.

Former Aberdonian Daryl Webb’s “Keep Pro Baseball: The Aberdeen Pheasants Baseball Team, 1945-1971” in South Dakota History (volume 46, number 2, 2016) is a great review of the team’s history.